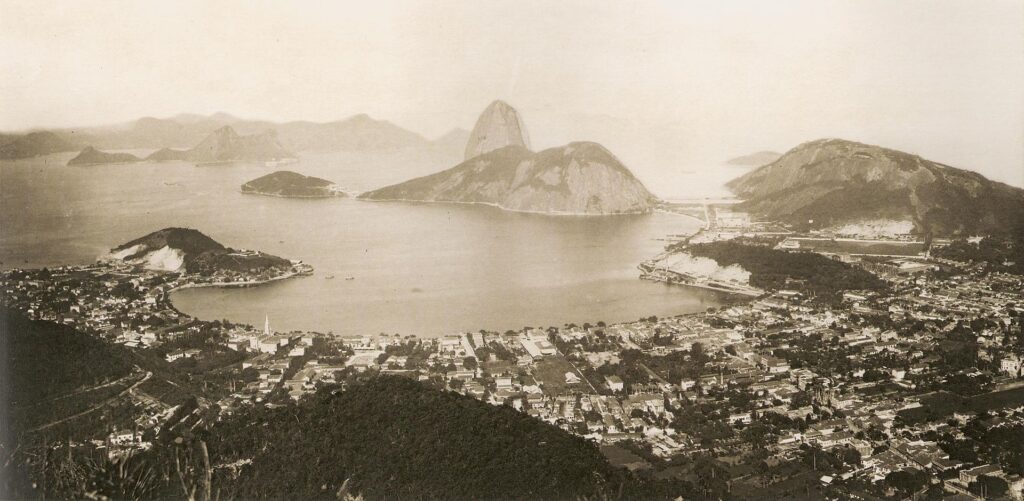

For nearly a century, Rio de Janeiro was the pulsating centre of the Brazilian Empire, a city where European opulence merged with tropical splendour. From 1808 to 1889, Rio served as the stage for events that defined Brazil’s imperial era, hosting Portuguese royals, shaping national identity, and setting the foundation for the modern nation. This period left an indelible mark on Rio de Janeiro, with its grand architecture, cultural institutions, and urban layout still bearing traces of the imperial legacy.

The Arrival of the Royal Court: A City Transformed

Rio de Janeiro’s rise as Brazil’s imperial heartland began with an unprecedented event: the transfer of the Portuguese royal court to Brazil. In 1808, fleeing Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal, Dom João VI and his entourage of over 10,000 people disembarked in Rio, turning a colonial backwater into a royal capital overnight. This marked the first time a European monarchy had relocated to the Americas, setting Rio apart from other colonial cities.

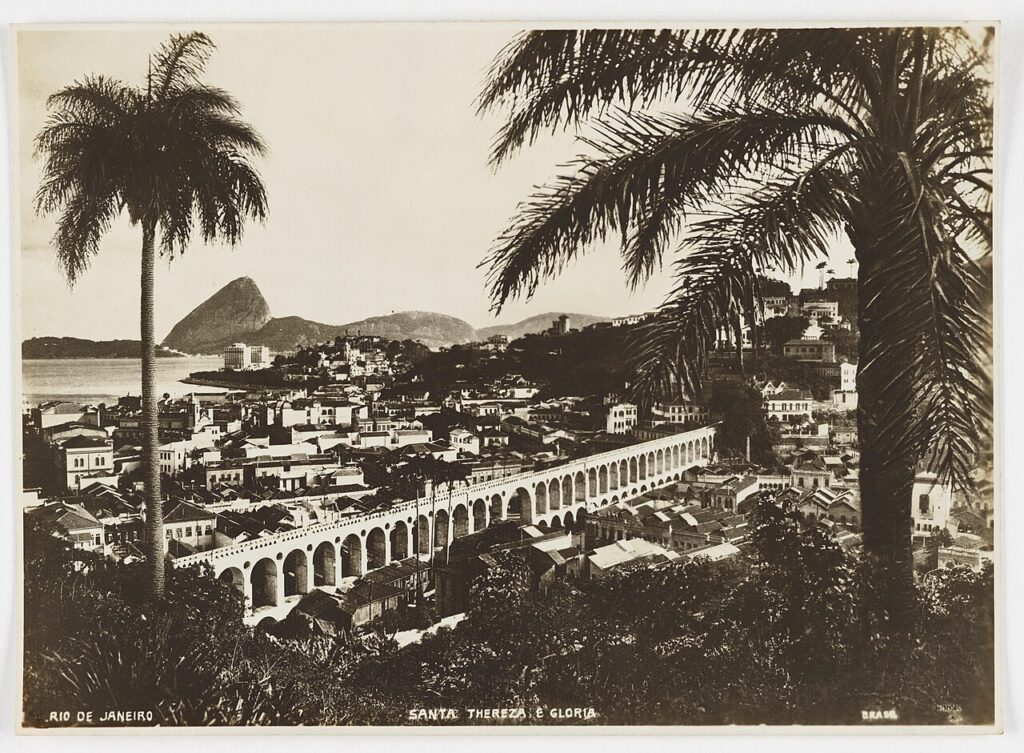

The arrival of the court sparked a dramatic transformation. The city underwent rapid modernisation to accommodate the royals and their entourage. Streets were widened, palaces constructed, and new institutions established, including the Royal Library of Portugal (later the National Library of Brazil) and the Botanical Garden, which became centres of knowledge and culture.

With Dom João’s presence, Rio ceased to be merely a colonial administrative centre. It became a vibrant political and cultural hub, symbolising a new era in which Brazil held greater significance within the Portuguese Empire.

From Colony to Empire: Independence and the Birth of an Imperial Capital

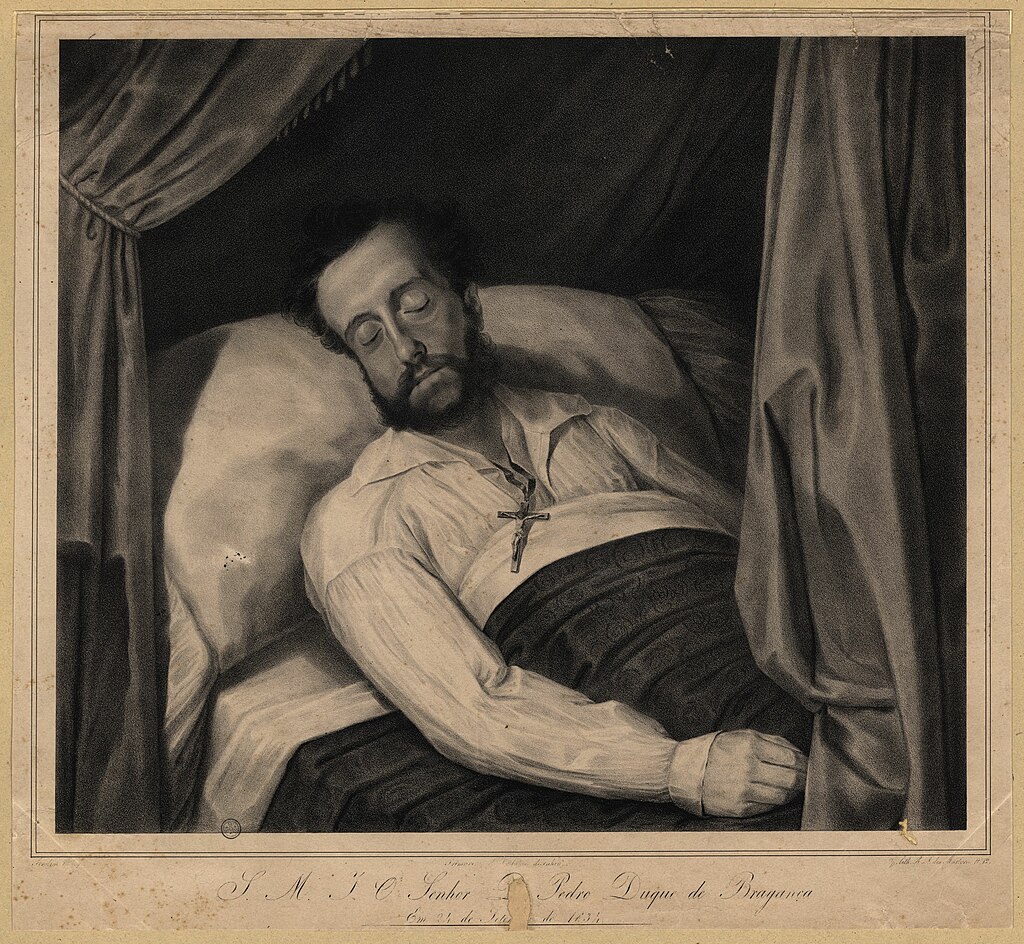

When Dom João VI returned to Portugal in 1821, his son, Dom Pedro I, stayed behind as regent. Faced with growing calls for independence, Dom Pedro famously declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal on 7 September 1822, shouting “Independência ou Morte!” (Independence or Death!) by the Ipiranga River in São Paulo. Shortly after, he was crowned Brazil’s first emperor in Rio de Janeiro.

As the capital of the newly independent empire, Rio de Janeiro took on a dual role: it was both the political nerve centre of the nation and a showcase for Brazil’s ambition to stand as an equal among the world’s great powers. The city’s imperial identity was solidified with landmarks like the Imperial Palace in Praça XV, where monarchs ruled and key political decisions were made.

The imperial family’s presence brought European cultural practices to Rio. The city hosted grand balls, operas, and artistic exhibitions, blending European sophistication with a uniquely Brazilian flavour. Yet beneath the surface of opulence lay stark inequalities, with enslaved Africans making up a significant portion of Rio’s population and providing much of the labour that sustained the imperial capital.

The Reign of Dom Pedro II: A Golden Age for Rio

The second emperor, Dom Pedro II, who ruled from 1840 to 1889, presided over what many historians consider Brazil’s imperial golden age. Educated, intellectual, and progressive (by 19th-century standards), Dom Pedro II fostered the arts, sciences, and education in Rio de Janeiro.

Under his reign, Rio flourished as a centre of innovation. The Academy of Fine Arts, founded during his father’s rule, became a beacon for Brazilian artists. Meanwhile, the emperor himself was a patron of science and technology, supporting projects like the laying of the first telegraph lines and the establishment of the Dom Pedro II Railway, which connected Rio to key agricultural regions.

The city also became home to architectural wonders that reflected its imperial status. The Paço Imperial, originally a colonial governor’s residence, was refurbished as a royal palace, while the construction of the Candelária Church and the São Francisco de Paula Church showcased baroque and neoclassical grandeur.

Despite these advancements, the contradictions of empire remained glaring. Slavery persisted as a central feature of Rio’s economy, even as abolitionist sentiment gained momentum. By the mid-19th century, Rio was the largest slave port in the Americas, and its streets were scenes of both human suffering and resistance.

Culture and Society in the Imperial Capital

Rio’s status as the imperial capital shaped its social fabric, blending European aristocratic customs with local traditions. The city became a cultural melting pot where diverse influences converged.

Music and Literature: During the imperial era, Rio was the birthplace of new musical styles like choro, a precursor to samba, which combined European melodies with African rhythms. Meanwhile, the city’s literary scene thrived, with writers like Machado de Assis, often regarded as Brazil’s greatest novelist, capturing the complexities of life in imperial Rio.

Education and Science: Dom Pedro II’s support for education led to the founding of institutions like the Pedro II School, which set new standards for Brazilian education. Rio’s intellectual community also benefited from the establishment of the National Museum, housed in the former São Cristóvão Palace, which became a centre for scientific research.

Urban Challenges: Yet Rio was also a city of stark contrasts. Wealthy elites lived in grand mansions, while the urban poor crowded into precarious tenements. Public health was a persistent issue, with outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera regularly sweeping through the city. These problems highlighted the disparities that characterised life in the imperial capital.

The Decline of the Empire and Rio’s Transition

By the late 19th century, the imperial system was increasingly out of step with Brazil’s changing social and economic realities. The abolition of slavery in 1888, while morally imperative, eroded the economic base of many of the empire’s supporters. Meanwhile, the rising urban middle class and military officers grew disillusioned with the monarchy’s inability to address modernisation demands.

On 15 November 1889, the empire came to an abrupt end when a military coup ousted Dom Pedro II, and Brazil was declared a republic. The imperial family went into exile, and Rio de Janeiro transitioned from an imperial capital to a republican one.

Although the monarchy was gone, the city retained much of its imperial legacy. The institutions, architecture, and cultural practices established during the empire remained integral to Rio’s identity, shaping its development well into the 20th century.

The Imperial Legacy Today

Rio de Janeiro’s imperial past is still visible today. Many of the landmarks from the empire have been preserved and repurposed, serving as reminders of the city’s historical significance.

- The Imperial Palace now functions as a cultural centre, hosting exhibitions and events that celebrate Brazil’s artistic heritage.

- The National Library, a jewel of imperial Rio, remains one of the largest libraries in Latin America.

- The National Museum, despite suffering a devastating fire in 2018, continues to symbolise the city’s scientific legacy, with efforts underway to restore its collection.

These sites, along with the city’s enduring cultural vibrancy, reflect the profound influence of Rio’s time as the imperial capital.

Rio’s Imperial Heartbeat

Rio de Janeiro’s history as the heart of Brazil’s empire is a story of transformation, ambition, and contradiction. From a colonial outpost to a bustling imperial capital, the city evolved into a centre of power, culture, and innovation. Its imperial legacy, though rooted in a time of inequality and exploitation, laid the groundwork for many of the institutions and traditions that define Brazil today. For those who walk its streets, Rio’s imperial heartbeat can still be felt in its architecture, its culture, and its enduring spirit.