Mato Grosso, a state located in Brazil’s central-western region, is often celebrated for its vast wetlands, expansive forests, and the unique cultural landscapes of the Pantanal and Cerrado ecosystems. But before it became a modern center of agriculture and industry, this land was home to a diverse range of Indigenous peoples who lived in these environments for thousands of years. Their cultures, ways of life, and profound knowledge of the land remain foundational to understanding the deep history of Brazil’s heartland.

Early Settlement: Ancient Roots of Mato Grosso’s Indigenous Peoples

The history of Indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso is deeply intertwined with the natural landscape. Archaeological evidence suggests that human presence in the region dates back at least 12,000 years, with some sites indicating occupation as far back as 20,000 years. The first inhabitants of this region were part of the broader wave of Indigenous groups that spread across South America during the late Pleistocene, settling in what are now the Pantanal, the Cerrado, and the forests of the southwestern Amazon.

Early settlers in Mato Grosso developed a deep relationship with the land. The region’s varied landscapes, from the vast marshlands of the Pantanal to the dry savannas of the Cerrado, required diverse survival strategies. These early peoples engaged in hunting, fishing, and gathering while also cultivating crops, with evidence of early agricultural practices, including the domestication of plants like manioc (cassava) and maize.

The Indigenous Groups of Mato Grosso

Today, Mato Grosso is home to several Indigenous groups, each with its own unique language, culture, and traditions. Among the most prominent are the Xavante, Kayapo, Terena, Bororo, Nambiquara, and Guarani peoples, though the state is also home to a number of smaller, lesser-known groups.

Xavante: Warriors of the Cerrado

The Xavante are one of the most well-known Indigenous groups in Mato Grosso. Historically, they inhabited the central and northern parts of the state, particularly the cerrado region, which they call home even today. Known for their warrior culture, the Xavante have long resisted outside pressures. Their social organization revolves around kinship ties and they have traditionally lived in large, communal villages.

The Xavante’s relationship with the land is integral to their culture, with extensive knowledge of local flora and fauna that informs their survival strategies. They engage in agriculture, planting crops like maize, beans, and sweet potatoes, but also rely heavily on hunting and fishing. Their intricate knowledge of the cerrado ecosystem has been vital in sustaining their communities for centuries.

Kayapo: Guardians of the Rainforest

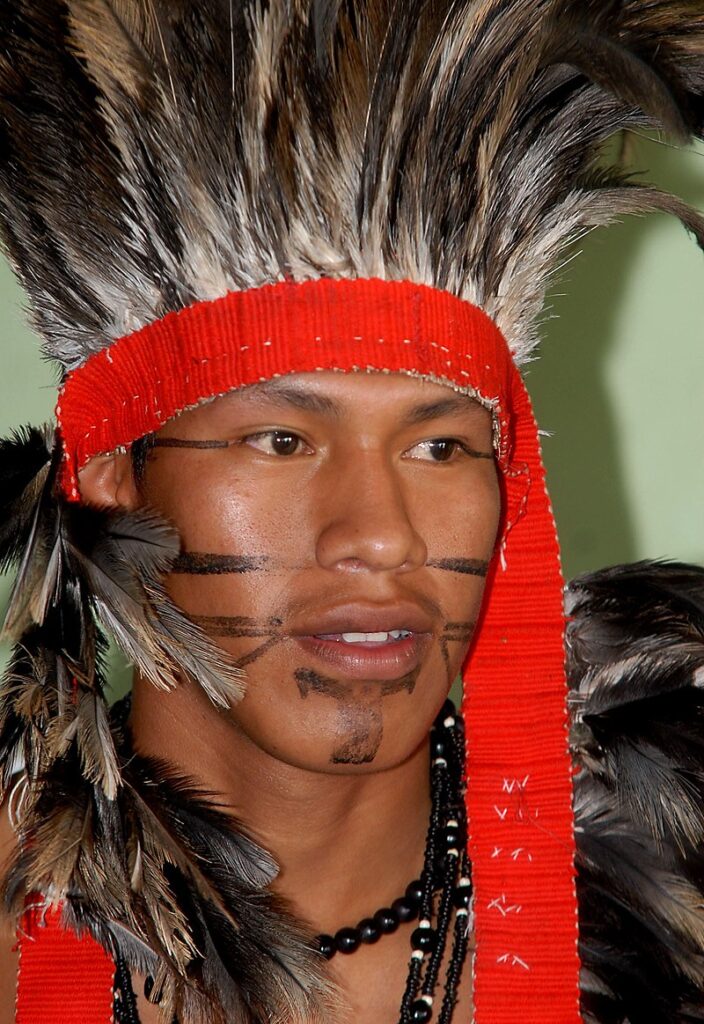

The Kayapo, also known as the Mebengokre, are another well-known group in Mato Grosso, with their territory extending into the neighboring state of Pará. They are famous for their elaborate body paint, ceremonial headdresses, and vibrant cultural traditions. Historically, the Kayapo have lived in the forests and river valleys of the Xingu region, though their land also stretches into the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Pará.

The Kayapo are renowned for their resistance to encroachment by outsiders, particularly during the 20th century when they became active in defending their territory against logging, mining, and dam projects. Their strong sense of community and dedication to preserving their way of life has been instrumental in their survival in a rapidly changing world.

Terena: Settlers of the Pantanal

The Terena people primarily inhabit the southern part of Mato Grosso, near the borders with Paraguay and Bolivia. Their traditional territory is located in the vast wetlands of the Pantanal, one of the largest tropical wetlands in the world. The Terena are known for their ability to adapt to the ecological challenges of the region, where they fish, hunt, and practice agriculture in a way that respects the balance of the ecosystem.

In the 20th century, the Terena became active in struggles for land rights, facing pressure from cattle ranchers and agribusiness interests that sought to appropriate their lands. The fight for land rights has been a defining feature of Terena life, and their ongoing advocacy for Indigenous autonomy is a testament to their resilience.

Bororo: The People of the Great Plains

The Bororo people traditionally lived in the plains and river valleys of Mato Grosso. Known for their complex social structures, the Bororo have a rich cultural heritage that includes music, dance, and an extensive mythology. The Bororo were one of the first Indigenous groups to encounter European colonizers, and their culture and ways of life were profoundly impacted by colonization.

The Bororo have long faced challenges in preserving their identity, but their continued resistance to external pressures has ensured that their traditions remain alive. Their knowledge of the environment, particularly in relation to the wetland areas of Mato Grosso, is a key part of their cultural resilience.

Nambiquara and Guarani: Diverse and Resilient

The Nambiquara and Guarani are other important groups in Mato Grosso. The Nambiquara traditionally inhabited the forests and savannas of the region and are known for their distinct languages and intricate customs. The Guarani, one of the most widespread Indigenous groups in South America, have a significant presence in the state, particularly in the western regions.

Both groups have had their lands increasingly encroached upon by farming and industrial development. Despite this, they have maintained a strong sense of community and continue to fight for their ancestral rights.

The Impact of Colonization

The arrival of the Portuguese and later the expansion of Brazil’s agricultural frontier had a profound impact on the Indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso. During the colonial period, the state became a center of trade in precious metals, such as gold, and was the site of various Indigenous slave raids. By the 19th century, the region saw the rise of cattle ranching and the development of vast plantations, which further encroached on Indigenous lands.

In the 20th century, Mato Grosso’s rapid economic development, particularly in the fields of agriculture, mining, and hydropower, led to increased conflict over land. Indigenous groups were often pushed to the margins, and their territories shrank as agribusiness interests expanded. The creation of the Xingu Indigenous Park in the 1960s was one of the first major efforts to protect Indigenous land in the region, though struggles for land rights continue to this day.

Modern Day: Resilience and Resistance

Despite centuries of colonization and land loss, the Indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso continue to thrive and resist the forces that seek to erase their cultures. Many groups have fought for legal recognition and land rights, and in recent decades, they have found strength in unity and advocacy at the national level.

Today, Indigenous organizations, such as the Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil (APIB), play a crucial role in protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso and beyond. They fight against illegal land invasions, deforestation, and efforts to weaken environmental protections, while also advocating for cultural preservation and education.

The history of Mato Grosso’s Indigenous peoples is one of resilience, adaptation, and deep connection to the land. From the ancient hunter-gatherers who first settled the region to the modern-day activists fighting for land rights and cultural preservation, the Indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso have endured immense challenges while maintaining their unique ways of life.

As Brazil continues to grapple with the legacies of colonization and development, the voices of Mato Grosso’s Indigenous peoples offer a crucial perspective on the importance of environmental stewardship, cultural diversity, and the rights of those who have long called this land home. Their history is not just a chapter of the past; it is a living, ongoing story that shapes the future of the state and the nation.